Is Mamdani’s victory the start of a political shift in America?

Is the result of the New York mayoral election a sign of a deep political transformation in the history of the United States? I’ll try to answer that in this piece.

For the first time, New York has a Muslim mayor. Across the Muslim world, this news has generated great excitement. The fact that the state in question is New York is telling enough. Everyone knows that New York is the most iconic American city—almost a global symbol of the full set of American values. And everyone also knows that Muslims today represent the most marginalized, vilified, and demonized culture and people on earth. While the U.S. has been leading that trend, the election of a Muslim mayor in a city that so directly embodies American values is nothing short of dramatic. To draw an analogy, it’s as if a leftist candidate had won the mayoral race in Berlin at the height of Nazism, when Hitler had come to power. As the U.S. slides deeper into fascism, Mamdani’s election doesn’t look all that different.

In the U.S. political system, the two main actors have long been the Republican and Democratic parties, representing the American right and left, respectively. There has never been room for a third party—and expecting that to change would be naive. The country’s political destiny remains in the hands of these two parties. So it makes sense to look at where Trump, as a Republican, and Mamdani, as a Democrat, stand within the political cultures of their parties.

Experience shows that when the U.S. economy is doing well, the differences between these two parties become nearly negligible. Both tend to field candidates firmly committed to the core principles of the American system. Compared to Europe, notions of right and left in the U.S. have always been softer, stripped of rigid ideological edges. To truly grasp the subtle distinctions between them, one must have lived within the American system for a long time.

Starting in the 1970s, this landscape began to shift. The Republicans radicalized rapidly, moving toward a neoconservative line—Reagan being the first example. This wave turned the Republican mainstream into a global aggressor. The “New Right,” as it was called, was later inherited by George H. W. Bush and his son. After the collapse of the Soviet bloc, Republicans grew even more aggressive.

This current was fueled by libertarian economics, which argued that economic forces should operate without any political or institutional interference. The inhuman outcomes, the vast and unsustainable inequalities it produced, were of no concern. Still, there were internal divisions. The libertarian values championed by the New Right remained deeply tied to a theopolitical, traditionalist worldview—especially regarding family and patriarchal norms, much like Evangelicalism. Yet within the traditional right, there were those uncomfortable with how libertarianism was eroding the authority of the state and paternalist values. Some intellectuals, inspired by thinkers like Mises and Hayek, sought to reconcile libertarianism with liberalism—but those efforts eventually faded to the margins.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, the Democratic Party—the standard-bearer of the American left—also began to transform. The ideas accompanying this shift came from the New Left. In Europe, the right (Thatcher, Kohl, etc.) was becoming more libertarian, while the left was becoming more liberal. The priorities of the liberal New Left were changing: the traditional concerns of inequality, class, and imperialism were fading. In their place came the notion of the state as the “father of all evils” and nations as the “mother” of cultural oppression. The new trend focused on the cultural issues believed to be suppressed by the state and national structures—topics like climate change, environmental collapse, gender and racial discrimination. Naturally, this put the New Left on a collision course with the New Right, which clung to its paternalist values. The conflict between them became increasingly cultural—a full-blown culture war. Under Clinton and Obama, the new Democratic leadership championed the New Left’s ideals, though in softened, diluted forms shaped by the American political culture.

By the 1990s, the systemic crises that began with the Soviet collapse finally hit Europe and the U.S. Libertarian capitalism had reached its breaking point. Global inequality had become intolerable, putting economic issues—long absent from the agenda—back at the center of politics. The Republicans tried to confront this with Trump’s brand of radicalism: a crude, mob-like populism that fused libertarian economics with militant theopolitical paternalism. It resonated with parts of society. The Democrats, however, were unprepared. Kamala Harris’s “Green New Deal” agenda failed to strike a chord. Their politics, shaped by middle-class sensitivities and fragile identity-based issues—like transgender rights—had grown detached from real social struggles.

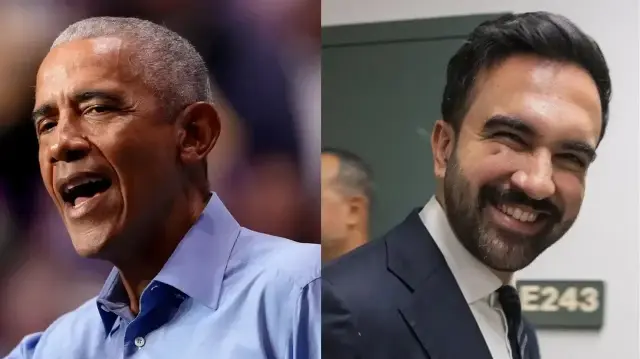

This is where Mamdani steps outside the mainstream Democratic line. He still echoes some of the New Left’s talking points, but he also brings something new: a focus on economic and social reform that genuinely connects with working-class realities. He’s gained the backing of figures like Sanders and Cortez, yet on the other side stand Soros and Obama. We’ll soon see which way the balance tilts.

Reklam yükleniyor...

Reklam yükleniyor...

Comments you share on our site are a valuable resource for other users. Please be respectful of different opinions and other users. Avoid using rude, aggressive, derogatory, or discriminatory language.